| 5 July 2020

Sounds triggered by events

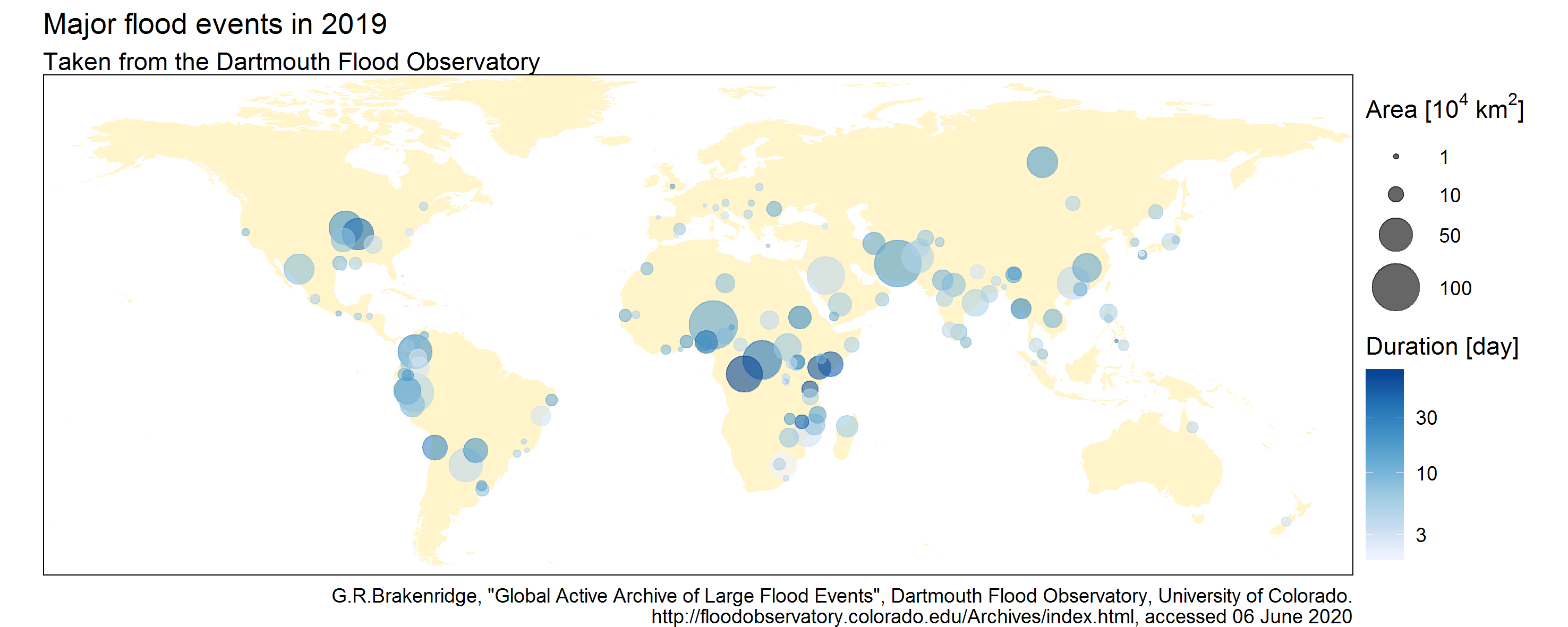

The map below shows the main flood events of 2019, their duration and the size of the flood-affected area (for further discussion of this dataset, see the post Sonification techniques: mapping data to pitch and volume).

This map does not say anything about the timing of the flood occurrences: did they all occur at the same time or regularly throughout the year? A natural way to provide this information is to animate the map, by making the points appear as floods occurred in real life. In other words, the drawing of a point is triggered by the occurrence of a flood.

As often, there is a sonification counterpart to this visualization technique: the occurrence of a flood may trigger a sound (like a splash for example) rather than the drawing of a point. This is known as sequencing a sound sample. The animated and sonified map looks / sounds like this.

Note that the attributes of the sound sample is used to represent some properties of the triggering event (using parameter mapping). The volume of the ‘splash’ is proportional to the flood-affected area. In addition, Southern hemisphere floods are heard in the right channel, and Northern hemisphere ones in the left channel (headphones or stereo speakers are required to hear this).

Groove is in the Earth

Sequencing essentially requires two ingredients: a sound sample and a time series to define triggering events. Short and percussive sounds are particularly well adapted, and many environmental datasets take the form of a time series. Consequently, sequencing provides the opportunity to turn Earth data into rhythmic patterns, by replacing the ‘splash’ by sounds from drums and cymbals.

Here are two examples based on similar hydroclimatic time series but with slightly different choices in terms of sequencing properties. The first example uses the Wagga Wagga dataset, which was already turned into a melody into this post. It is now turned into a rhythmic pattern as follows: a bass drum is kicked when precipitation is low, a snare when it is high, and the temperature controls the volume. A basic hi-hat pattern is added and this gives the Wagga-Wagga Groove.

The second example uses 69 years of seasonal data near Marseille, France:

- Temperature data control the volume of the hi-hat sound sample, leading to a very regular background rhythm.

- A snare sound sample is played every time atmospheric pressure exceeds some threshold, with the volume being proportional to the threshold exceedance. This variable is much more irregular than temperature, leading to a more erratic rhythmic pattern, with sometimes several hits in a row, and sometimes long periods with no hit at all.

- Similarly, a bass drum is played every time precipitation is below some threshold, with the volume being proportional to the precipitation deficit.

Of course, sequencing is not limited to percussive patterns, although it is probably a good place to start. Brian Foo’s project data-driven DJ is a great illustration of the potential of data-driven sequencing for creating sounds and music.

Practical tools

Sequencing sound samples has been at the core of several musical genres such as electronic music or hip-hop. Consequently, a huge variety of devices is available to create musical sequences, ranging from old-school drum machines and samplers to audio musical software (e.g. audacity for a free open-source one). These can all be used to create and arrange sequences ‘by hand’, but for larger datasets, a programming language is necessary.

Sound samples are represented as waveforms which are simple time series that can be easily manipulated using any programming language. I am personally using the R language and its package tuneR to perform basic operations such as reading sound samples, controlling their amplitude (which itself controls the volume of the sound), repeating and combining them to create sequences, etc. I developped the sequenceR package for this purpose.

This is sufficient to get started with the most basic actions involved in data-driven sequencing, but many additional tools exist to perform more advanced audio manipulations (e.g. filters, equilizers, reverberation, distortion and many more). In Python the libROSA package contains many functions for audio analysis. There also exists several programming languages entirely devoted to audio synthesis and sequencing, for instance Csound, ChucK or SuperCollider. These are certainly the most complete, efficient and powerful tools, but as a beginner I found them a little bit overwhelming.

Author: Ben

Codes and data: browse on GitHub